White People Need to Own Our Discomfort

For those of us who are white, the role we find ourselves occupying is that of white supremacy. In her book, What Does It Mean To Be White?, Robin DiAngelo describes white supremacy as:

“……. not refer(ing) to individual white people per se and their individual intentions, but to a political-economic social system of domination. This system is based on the historical and current accumulation of structural power that privileges, centralizes, and elevates white people as a group….I do not use it to refer to extreme hate groups. I use the term to capture the pervasiveness, magnitude, and normalcy of white dominance and assumed superiority.”

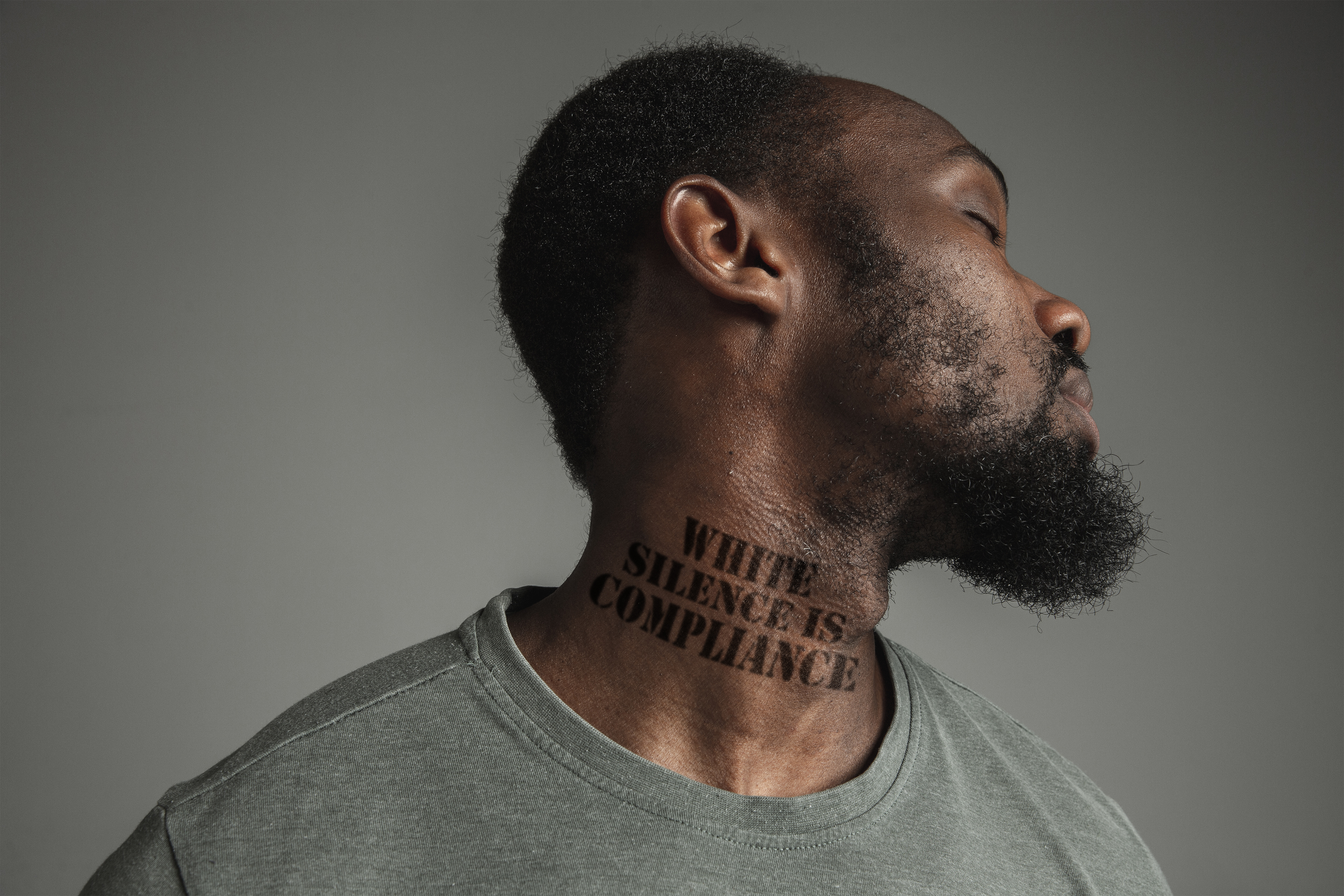

To address this historical white dominance and assumed superiority, Resmaa Menakem, in his book, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, states two powerfully, related truths: that we must start with healing our own bodies, and that—to survive as a country—it is inside our bodies where the real battlefield lies. We as white people need to admit to ourselves and to each other that we see white people as the norm and people of color as a deviation from that norm. Accordingly, we must own that this distorted view persistently sends messages of white superiority as well as black and brown inferiority. We must acknowledge the stories we tell ourselves about people of color being a threat to our safety—especially black men. And we must hold ourselves accountable for the ways in which this misconception has resulted in the neuropathways of authoritative white men reflexively responding with aggression and violence when interacting with people of color.

As practitioners and trainers we are uniquely positioned to use trauma-informed principles to address historical trauma. Those principles, which are core ingredients in the Risking Connection curriculum, include feelings management, co-regulation, connection through empathy, and instilling hope. We also know that to most effectively provide trauma-informed care, it is important that we start by recognizing our own visceral reactions to the work we do, including the ways we have each contributed to historical trauma through our personal and professional roles.

For me, when I heard people of color describe the injustices they have experienced at the hands of whites, I had to notice how I reflexively reacted with the thought, “Well, that’s not me. I’m not a racist.” I had to stop and think about how that reaction was adaptive; it allowed me to deny the shame that was welling up in me and causing me great discomfort. It also provided me refuge from the threat that I may one day become the oppressed if I were to give up the power that I thought was rightly mine. When I embraced all the uncomfortable feelings and emotions—when I digested them and owned them—I was then able to make room for healing the pain of historical trauma.

With my own reactions regulated, I was then able to see the pervasiveness of racism and social injustice. I was able to hear with an open heart the layers of pain expressed by my clients of color. When I walked alongside my African American colleagues and experienced first-hand what their daily lives are like in a white-dominated society, I stopped excusing white people’s behavior as well-intended even though it was ill-informed. I was able to own my white privilege with less shame and more commitment to action. I was able to be present and see the injustices before me.

Those injustices before me were plentiful and they played out daily. My African American colleagues and clients were my teachers. For that I have this monolithic regret: for putting them in a position to repeatedly have to teach us white people about their lives, when in reality it is on display every day if we are paying attention. This is what I witnessed when I started paying attention:

- De-humanizing: At lunch, the waitress made eye-contact with me and took my order promptly, while my black colleagues were either ignored or forgotten.

- Profiling: My black colleagues were followed around a store by an employee while I was left alone to do my shopping.

- Fear: The fear in one black colleague’s eyes as she told me about the time she spent having “the talk” with her 10-year-old grandson and the pain it caused her to look into his eyes and tell him that the color of his skin poses a threat to white people. That when he is confronted with an authority figure, he should immediately subjugate himself to that authority regardless of his innocence.

- Lost Hope: A young person of color excited to study mortuary science, only to drop out because he feared he could not control his anger and rage if one more white woman crossed the street as he approached on his way to school or one more white person asked him to clean the tables in the cafeteria where he was studying, in the assumption that he was a custodian.

- Injustice: When I visited juvenile court, black boys and girls being afforded the privilege of innocence to a far lesser extent than their white counterparts (Goff, 2014).

- Inequities: In oppressed communities, schools plagued with peeling paint, rusted lockers and few if any enrichment activities.

- Rage: Mothers denied access to their child’s body after a homicide because of the police crime scene tape that prevented them from gaining some source of comfort and dignity.

I ask all of you, as white trauma-informed practitioners, to notice your reactions. What is going on in your body that prevents you from:

- providing a safe place and a willingness to hear the rage that accompanies a life of degradation and humiliation at the hands of others?

- breaking the cycle of violence by providing techniques to metabolize the rage and injustice, so it does not become a contagion for your clients of color, and by extension their families and communities?

- facilitating the building of new neuropathways by becoming a unique experience for people of color, counter to what they experience in society at large?

- speaking up when systemic racism rears its discriminatory head?

By starting with ourselves, we will then be able to truly hear the pain that people of color have been asked to regulate for centuries. When we approach our own discomfort with curiosity rather than fear, we may then realize the wish of one young man of color:

“I long for a world where my people and I can step outside and feel the same safety and comfort as the man/woman to our left and right. When the day comes that the color of my skin creates no misconceptions on the value of my life, the U.S. will truly be able to be called “The Land of The Free-for everyone.” (Kurt Adkins)

Resources

Di Angelo, R. (2016). What does it mean to be white?: developing white racial literacy. New York: Peter Lane.

Goff, P. et al., (2014). The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children, 106 j. of persoNality & soC. psyChol. 526 (2014).

Hicks-Ray, D. (2004). The pain didn’t start here: Trauma and violence in the African American community. TSA Communications

Menakem, R. (2015). My grandmother’s hands: Racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. Las Vegas, NV: Central Recovery Press

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, NY: Penguin Books.